Under the Radar 2006-07-20 – Muse

To cite this source, include <ref>{{cite/undertheradar20060720}}</ref>

Muse

Interview by Marcus Kagler

Photos by Derrick Santini

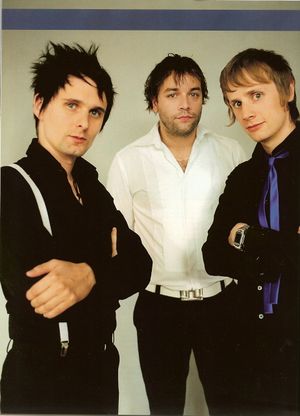

After three albums and almost ten years together, the past three years have finally borne fruit for Muse (vocalist/guitarist Matthew Bellamy, bassist Chris Wostenholme, and drummer Dominic Howard). Their third album, 2003’s Absolution (released in America in 2004), broke the English trio into the mainstream and heralded the worldwide success that would lead them to the prized headliner slot at Glastonbury and two years of exhausting tours. Now that the band has completed their fourth and most anticipated album yet, Black Holes and Revelations, Bellamy is ready to start up the juggernaut of press and tours once more. Bellamy, who is currently living in northern Italy, was concerned with England’s World Cup progress when Under the Radar got him on the phone, but he was also game for discussions on the change in Muse’s sound, the necessity for political revolution, and how a little bit of Italy crept into Muse’s epic, progressive battle cries.

Under the Radar: The new record is a lot different. You guys really pushed your sound in a lot of different directions. Where did some of these musical influences come from?

Matthew Bellamy: I’ve always been a big fan of instrumental music in general. For me, to write a song, I need the music to have some kind of atmospheric feel or create some kind of imagery in my mind. Not every song, but I think me as a listener, I tend to listen to quite a lot of instrumental stuff – like Philip Glass and some classical bits I’ve listened to over the years. Recently I discovered some music now that I live in Italy. A lot of it sounds like [Ennio] Morricone from the south of Italy. Music from Naples and Sicily is a kind of folk music, really. It sounds like it’s been influenced by other continents like North Africa and even some Middle Eastern influences are in there. Some of the songs have this flamenco influence because that’s what I used to play when I was young. I never hand any lessons on any instruments, but when I was about sixteen or seventeen, I had a few lessons on the flamenco guitar, and I always fancied getting a little bit of that into the band.

I think the electronic slide has been creeping up on us. I think you can hear it on the last album, but this time we made an effort to push it more and bring some of it into [the] rhythm section of the band, [as in] a song like “Supermassive Black Hole,” where the drums are quite electronic-orientated in the way they have been recorded and stuff, and that’s quite different for us really.

I’ve been listening to a man called Felix Cuban. He’s pretty cool. He makes this kind of strange, slightly comical electronic music which sounds very good to me. In terms of rock stuff, I’ve been influenced by an American band called Lightning Bolt. It’s like a two-piece kind of thing, and they manage to get an extremely powerful sound out of just bass and drums. That’s something we try to achieve when we can in songs, because the bass and drums can have the power of a full band, so I don’t have to play chunky stuff to kind of fill things up. I can play stuff that’s more in the upper regions and are different to melodies rather than just playing power chords all the time – kind of like a Death from Above 1979 sort of thing. We went into this album with the intention of changing ourselves a little bit; not just doing what has become familiar, which is an easy thing to do. Once you’ve done three albums, it’s quite easy to sort of just try to regurgitate what you’ve done before. It’s more a challenge if you find a new style of playing.

You were in the studio for a long time. Did that allow you the freedom to explore and change your songwriting?

We went to the south of France for a while. We went there initially to actually record the album, but we spent most of the time there writing songs and rewriting old songs. We realized the songs needed some work. We were changing them so they would go in different directions. We spent nearly two months there. It was important that we stay in a secluded environment like that, because I don’t think we’ve ever actually lived together while writing. Usually we’ve written songs before we go into the studio. This time we were living together in this chateau-type of place in the south of France and it was nice to get away from it all, to get away from all the things that influence your life. We were really cut off from the world in a way. There was no TV or internet or telephones or anything. It was all very cut off. You can’t get a mobile signal there. We had nothing better to do than just make music, really, and I think that’s quite a good way to write. Pretty much all the writing took place there, but the actual recording took place in New York.

This record is almost an overtly political album. What drove you to make that decision now?

I wasn’t very interested in politics while growing up. But in the last few years there are certain tings going on all around us, which is quite obvious to see. Obviously since September 2001, a lot of things have been changing in the world, especially with the U.K. government and the American government. They’ve been using this as an excuse to bring martial law and take away a lot of freedoms from people. A lot of the foundations they are building have been proven to be manipulated like that whole dossier thing that happened in England – that Dr. David Kelly or whatever, who let loose about that fact that the reason to go to war in Iraq had actually been sexed up or manipulated, basically. Tony Blair manipulated it to inspire the public to go to war. Things like that that really alarmed me. In the last few years, I’ve really woken up to the fact that we are actually quite manipulated as the general public by our governments and by the media as well, and particularly the clandestine organizations which run to black budgets in the CIA, FBI, NSA and others. You never see where they get their information from. It’s always, “We have to protect our sources.” In some ways, that gives them the right to make up whatever they want; then they can say, “By the way, this came from a secret source we can’t tell you about,” and next thing you know, they are telling us there are nuclear weapons in Iran and so forth, and before you know it we are going to be in a full world war. It’s definitely an interesting time. Politics isn’t something that’s always been a part of my life, but in the last few years I’ve just been observing what’s been going on all around us, and it’s quite alarming.

Is the song “Take a Bow” about Blair, Bush or both?

[Laughs] You could easily aim it at those types of people. There’s loads of them out there. It’s about the people who are kind of manipulating public opinion to their own means, which isn’t always the best for the people of the country. There’s obviously a global agenda taking place as well as an agenda to obtain the last bit of oil because all of our economies are absolutely dependent on oil. You can easily say that song is aimed at wishing, “Wouldn’t it be nice if these people did actually have to pay the consequences?” They have to pay the consequences for their actions. In England, that whole dossier report thing was made into a bit of a spoof in the end. People were just kind of laughing at it, saying how ridiculous it is that the government can get away with that kind of manipulation. You know, 15,000 people have died in Iraq because of that, and it’s a crime. I shouldn’t go on forever about that kind of stuff, because the band isn’t all about that. I think it’s just a few songs that have come from that angle.

In “Take a Bow,” you can hear the people who are at the bottom of the pyramid, who haven’t got any power, and they have this feeling of powerlessness, a feel I have quite often, about some of these events – this sense of, “What can I do about this?” It seems like no one is listening. A million people protest, and nothing really happens. Songs like, “Assassin,” “City of Delusion,” “Soldier’s Poem,” “Take a Bow” – I think these four songs are the most connected in that [political] way. I think there are other songs that deal with other subjects and more personal matters. “Starlight” is a more personal song about what it’s like to be on the road for a long period of time – you feel like you’re losing touch with who you are, and that kind of vibe.

I think underneath the album there is an optimism which I think is different from previous albums. I think on the previous albums, the despair was more dominant throughout. This time there is a kind of strength, and I’m hoping to find it in myself, but also in the music. There is this feeling of waking up and trying to fight back, or it’s time to actually try and change yourself and the things that are going on around you. I think to me that’s very optimistic, this strength. Sometimes it comes out in a very violent form, like in song, like “Assassin,” or a more obvious form like at the end of “Knights of Cydonia,” when I’m just saying, “No one is going to take me alive” and all that kind of stuff. I think it’s the strength of the human spirit fighting against the forces that are manipulating it.

Muse has never gotten into this many different genres of music on a single album before. Did you have to rethink the way you write music for this album?

I think this is the first album where we’ve gotten really active in the engineering and production of it. That to me is where the real innovation for us was. A song like “Supermassive Black Hole” – if you heard us just jamming that in rehearsal, it would song like some kind of Rage Against the Machine riff, maybe a softer Rage Against the Machine riff; it’s quite a bluesy riff. But the way we produced it – with all these electronic elements, and really trying to get our heads around a lot of synthesizers and programming equipment – that process made the song completely different. In some ways the writing was still very natural. The writing was just coming from inside of us, and it’s just expressions of how we feel about the world around us. The way we treated it, the way we produced it, the way we recorded it, arranged and played it – that was the new ground for us.

Do you think that by the time you’ve reached this point in your career it’s more important than ever to keep pushing forward and experiment with new sounds?

I think in some ways, and it’s something I’ve tried to achieve on every album, I don’t think we ever really fit in with what was going on in the rock world. When we started out, it was all Britpop, with bands like Oasis and Blur. And then Nu-Metal became very dominant in the rock world, and then the softer bands like Coldplay, and obviously you got the garage stuff like The Strokes going on. I like all of these types of music…mostly. Some have gone and some have stayed and some have disappeared, obviously, but we’ve never necessarily blended in with all of them. Musically, we’ve felt we’ve been relatively far way from other bands.

“City of Delusion” is definitely a highlight track on the record. Where did that song come from?

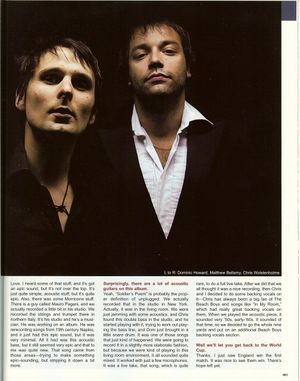

I wanted to do a song that was a bit more acoustic-based. That song was almost entirely acoustic at one point. But when the band started playing it together, it just started to get more and more rocking the more we played. Originally, when we played [the song], it had more of a Latin rhythm to it. But then it started getting heavier and heavier and wound up being a rock track. I remember someone played me a band called Love. I heard some of that stuff, and it’s got an epic sound, but it’s not over the top. It’s just quite simply, acoustic stuff, but it’s quite epic. Also, there was some Morricone stuff. There is a guy called Mauro Pagani, and we actually recorded a little bit in his studio. We recorded the strings and trumpet there in northern Italy. It’s his studio and he’s a musician. He was working on an album. He was rerecording songs from 19th century Naples, and it just had this epic sound, but it was very minimal. All it had was this acoustic bass, but it still seemed very epic and that to me was quite new. That song came from those areas – trying to make something epic-sounding, but stripping it down a bit more.

Surprisingly, there a lot of acoustic guitars on this album.

Yeah, “Soldier’s Poem” is probably the proper definition of unplugged. We actually recorded that in the studio in New York. Actually, it was in the living room. We were just jamming with some acoustics, and Chris found this double bass in the studio, and he started playing with it, trying to work our playing the bass line, and Dom just brought in a little snare drum. It was one of those songs that just kind of happened. We were going to record it in a slightly more elaborate fashion, but because we were kind of playing in this living room environment, it all sounded quite mixed. It worked with just a few microphones. It was a live take, that song, which is quite rare, to do a full live take.

After we did that we all thought it was a nice recording, then Chris and I decided to do some backing vocals on it – Chris has always been a big fan of The Beach Boys and songs like “In My Room,” which had really great backing vocals on them. When we played the acoustic piece, it sounded very ‘50s, early-‘60s. It sounded of that time, so we decided to go the whole nine yards and put on an additional Beach Boys backing vocals section.

Well we’ll let you get back to the World Cup.

Thanks. I just saw England win the first match. It was nice to see them win. There’s hope left yet.